“I was basically an anti-fascist and socialist minded. […] In a socialist state everybody would have some sort of social justice to be entitled to work and to make a living, no matter what. To get out of the debasing condition that we had in Canada [during the Great Depression]. […] That was the main theme, to look forward to something more humanitarian.”

Hans Ibing, interview with Art Grenke, 1980

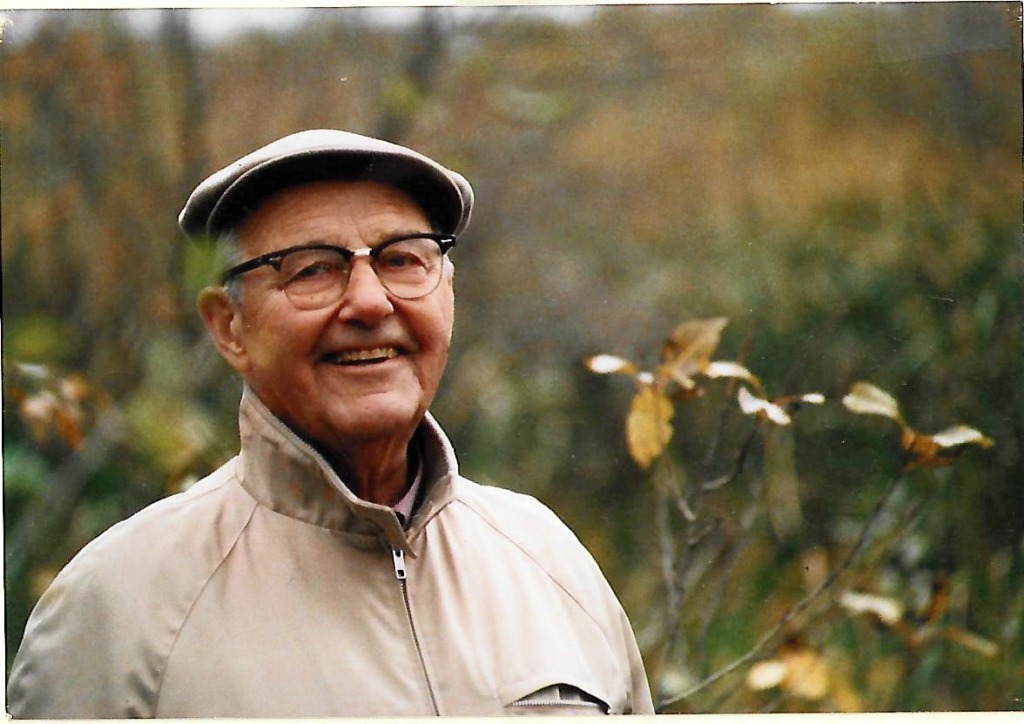

Hans Ibing was a German-born political leftist who worked as a newspaper printer in Toronto from the 1940s to 1970s. A man with strong political convictions, Ibing spent much of his life fighting for his beliefs, particularly anti-fascism. This outlook led him to become an active participant in various German-Canadian community groups, join the Canadian Communist Party, and even volunteer to fight in the Spanish Civil War. Although Ibing has been largely forgotten in German-Canadian history and memory, his story is quite well documented—especially for someone who thought of himself as “just an average person.”

Over his lifetime, Ibing participated in three oral history interviews, two of which are available through Library and Archives Canada. In 2018, labour historian David Goutor (who is married to Ibing’s granddaughter) used these interviews in conjunction with stories he had been told around the dinner table, Ibing’s personal papers, and archived material to write a biography of Ibing.

Born in Mainz in 1908, Ibing was exposed early on to politics through his father, who held various elected offices as a member of the Social Democratic Party. Although Ibing was generally apolitical during his youth, he speculated that his father’s views on social issues likely influenced his own involvement in social movements later in life. It was also during his early years that Ibing developed a fundamental dislike for fascists and members of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party, whom he described as bullies.s.

“I was anti-Hitler right from the start. I was anti-Hitler while I was still in Germany. As a young fellow I hated their arrogance, I hated their bullying, and I hated the fact that the worst elements were members of the [Nazi movement].”

Hans Ibing, interview with Art Grenke, 1980

In an attempt to distance himself from the emerging Nazi movement and to find better employment opportunities, Ibing immigrated to Canada in 1930. It was here that Ibing came into his own politically. Motivated by the inequalities and injustices that he observed during the Great Depression, Ibing joined a variety of workers’ organizations and ultimately the Communist Party of Canada in 1935. The next year, he volunteered to fight in the Spanish Civil War as a member of the International Brigades. In his interviews, Ibing acknowledged that his decision to go to Spain had been made partly through youthful optimism and naïvité, but this in no way detracted from his steadfast anti-fascist beliefs.

“The situation in Canada was so hopeless, and here there was something to do. At least you had the chance to fight for social justice or to establish something in Spain. The war was the Republic against fascism, and fascism was the great enemy.”

Hans Ibing, interview with Art Grenke, 1980

Although Ibing never regretted volunteering to fight in Spain, he returned to Canada disheartened after Franco’s victory over the Republic. He was particularly disappointed in the Western powers’ official policy of non-intervention, believing that the policy had doomed any chance of Republican success. He also never forgot the widespread misery and tragic loss of life that he had witnessed in Spain. Despite this, Ibing was fully prepared to enlist in the Canadian army when Canada declared war on Germany in 1939. When he approached the Air Force he was, however, turned away; Germans were not trusted to join the Allied war effort. Even labelled as an enemy alien, Ibing was still a strong advocate for anti-fascism. He was an active member of the German Canadian League, a group of Germans who spoke out against the Nazi movement and tried to drum up support for the Allied forces among German Canadians. After he married Sarah Kasow, a Jewish woman, in 1942, the pair also worked with advocacy groups to combat anti-semitism.

From the onset of World War II, Ibing increasingly took issue with the official Communist party line. Working at Canada’s main Communist print shop, Ibing was well integrated in Communist circles but found the Soviet Union’s reaction to European fascist aggression to be hypocritical and self-serving. Once the war ended, Ibing maintained his Communist Party membership but became increasingly non-doctrinaire. It wasn’t until 1953, after a trip to East Germany, that Ibing fully lost faith in the Communist cause and became politically inactive.

By the 1950s, Ibing had moved to the suburbs of Toronto with his wife and daughter. He stopped working for the Communist paper and instead found a job with the Globe and Mail and later, the Toronto Star. He retired at the age of 66 and went on to enjoy a long retirement where he kept in close contact with his daughter and grandchildren. Ibing died in 2009, shortly before his 101st birthday. Until his death, Ibing maintained his firm belief in socialist ideals.

Ibing’s memories were remarkably stable across the interviews he did despite taking place decades apart. He described his general life story consistently and seemed to relish the opportunity to tell anecdotes that were particularly amusing or exciting. For example, the humorous account of how Ibing was able to secure a stable job as a delivery driver, despite not knowing how to drive, shows up in at least two of his interviews and the biography by Goutor.

The one topic Ibing was more reluctant to look back on, since it always brought to mind memories of great suffering, was the Spanish Civil War. Ironically, this seemed to be the topic that interviewers were most interested in hearing him speak on. All three interviews he participated in spent a significant amount of time delving into his experiences in Spain. Through these accounts, it is clear that Ibing had very little interest in reminiscing on the history of military battles. Instead, he described the Civil War as a single point in the larger fight against fascism, focusing on the injustices that took place.

Ibing’s commitment to his principles and his willingness to fight for what he believed in were extraordinary. Whenever possible, Ibing’s decisions were shaped by his desire to help make the world a better place and extend the fight for social justice. In his old age, Ibing still stood by the principles that had made him volunteer for the International Brigades in 1936. He didn’t have any regrets.

“I’m not sorry for anything I did or belonged to. I think I always did it in good faith. I always thought I was doing the right thing and never did anything that I didn’t think was the right thing to do.”

Hans Ibing, interview with Art Grenke, 1980

Pictured: Hans Ibing, picture provided to GCS by his daughter, Irma Orchard.

Interviews and Books:

Goutor, David. A Chance to Fight Hitler: A Canadian Volunteer in the Spanish Civil War.” Toronto: Between the Lines, 2018.

Ibing, Hans. “Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, Radio: Spanish Civil War Oral History Tapes.” Interview By Mac Reynolds. Library And Archives Canada. March 4, 1965. https://recherche-collection-search.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/home/record?app=filvidandsou&IdNumber=351497&new=-8585540567172605901

Ibing, Hans. “German Workers And Farmers Association.” Interview By Art Grenke. Library And Archives Canada. April 11, 1980. https://recherche-collection-search.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/home/record?app=filvidandsou&IdNumber=418314

Petrou, Michael. Renegades: Canadians in the Spanish Civil War. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2014.

–Sophie Sickert, Senior Research Assistant, University of Winnipeg

____________________________________________

citation: Sickert, Sophie, “Hans Ibing: A German-Canadian Fighter for Social Justice,” German-Canadian Studies: The Blog of German-Canadian Studies at the University of Winnipeg. February 8, 2023. https://uwgcs.wordpress.com/2023/02/08/hans-ibing-a-german-canadian-fighter-for-social-justice/